Central location of new homes and workplaces in combination with straighter and faster public transport lines with a higher frequency, although it provides somewhat longer walking distances to stops than today.

That is the recommendation for small and medium-sized Norwegian cities that want to develop their cities in accordance with the emission goal of zero growth, according to a new TØI report. These are the same measures that have been shown to work well in larger cities.

Most of the research in this field has been conducted in and for large cities. Small and medium-sized cities need knowledge about area development and development of public transport services based on surveys conducted in cities of the same size. The purpose of this project has been to develop such knowledge. Among the case cities in the project we find Oslo, Bergen, Stavanger / Sandnes, Trondheim, Drammen, Fredrikstad / Sarpsborg, Kristiansand, Tønsberg, Ålesund, Arendal, Haugesund, Bodø, Hamar, Lillehammer, Mo i Rana, Kongsberg, Molde, Harstad, Gjøvik, Kristiansund, Alta, Elverum and Levanger.

Same patterns in smaller cities as in large

Researchers at TØI have studies how area development and the development of public transport services affect how people travel in small and medium-sized cities. This is useful knowledge when cities are planning and developing land use and transport systems in line with the zero growth goal, and in the effort of facilitating more people to travel by public transport, cycle and walk.

In the report, the researchers examined the connections between urban structure and travel behavior in 20 Norwegian urban areas, ranging from Oslo (980,000 inhabitants) to Elverum (15,000 inhabitants). The analyzes were performed with data from the national travel habits survey. The results show that the mechanisms from studies of large cities work in the same way in the smaller cities. The patterns are the same, but the effects are somewhat weaker and less consistent in the smaller ones than in the larger cities.

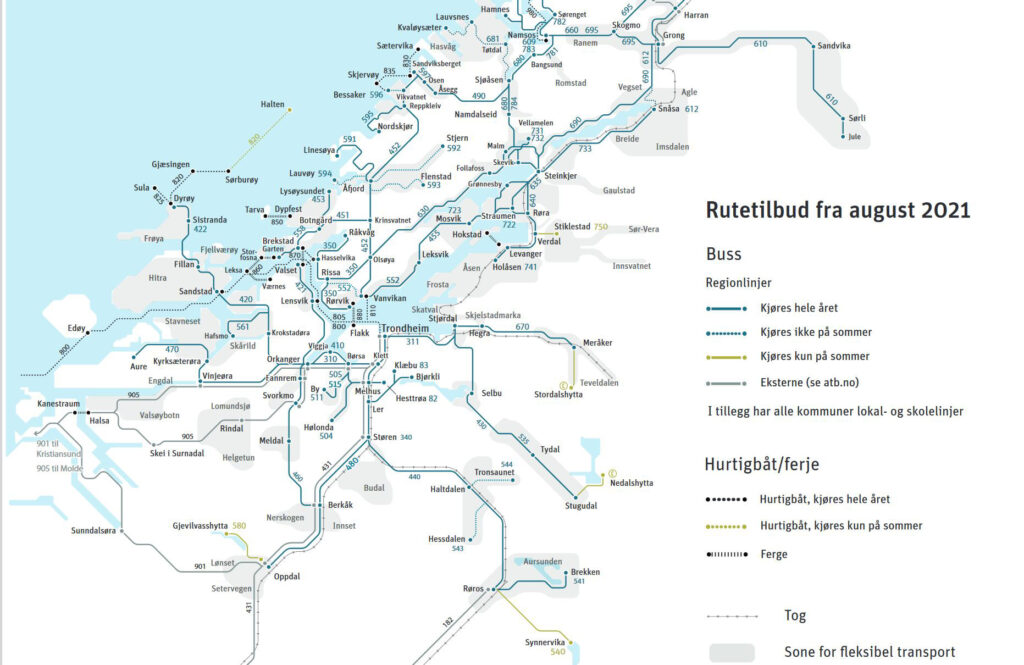

Car shares and commuting distances increase in line with how far away the homes and workplaces was situated from the city center in smaller cities following the same pattern as in large cities. The average walking distance to public transport stops increases with increasing city size, from 328 meters in Hamar to 528 meters in Oslo. Several small and medium-sized cities have switched to simpler, smoother and faster public transport routes with a higher frequency and reduced the offer of less used routes. In all but one city, this has resulted in increased passenger numbers, in some cases significant increases.

Develop the city centers

Researchers have also examined plans in four cities that have changed or are in the process of strengthening their public transport services. The plans in all the cities contain measures that strengthen the effect of the public transport improvements, but also measures that will help reduce the opportunities for public transport investments pay off in full.

The most important recommendation for small and medium-sized cities is that they can safely lean on the experiences developed over many years, based on studies conducted in larger cities around the world. Important measures are to develop new housing, jobs and trade in the city center and inner city and stop the development in the outer parts of the urban areas. Also, create a public transport service that is easier, faster, straighter and with more direct lines with a higher frequency, although it can lead to somewhat longer walking distances to the stop. Furthermore, facilitate for cycling and walking, and implement restrictive measures against car traffic.

Summary results

- Lower car shares and higher public transport and pedestrian shares is connected to increasing density (population plus jobs) at city level.

- Proportion of journeys made by means of transport other than car was higher to and from homes and workplaces located in the city center and inner city compared with outer parts of the cities.

- The commuting distances were clearly shorter among those living in the cities compared to those living in the outer parts of the cities.

- Shorter commuting distances to workplaces that are centrally located.

- Travel to / from hub areas in the cities was longer and more car-based than to the inner city and the city center, and some hubs were also longer and more car-based than to the outer parts of the cities.

- Average walking distance to local public transport increased with city size from 4.1 to 6.0 minutes and from 328 to 520 meters.

- Walking distance to a stop at both ends of the public transport journey affected the probability of traveling by public transport to work.

- Higher frequency, higher speed and more direct connections are more important than shorter walking distances to stops.

- There are plans for the development of the cities that reduce the effects of public transport investments.

Text: Hanne Sparre-Enger, TØI

Read more:

Aud Tennøy, Eva-Gurine Skartland, Marianne Knapskog, Frants Gundersen & Fitwi Wolday (2021): Public transport and urban development: Improving public transport competitiveness versus the private car in small and medium-sized cities. TØI report 1860/2021. (In Norwegian, with a summary in English.)

Contact:

Aud Tennøy

ate@toi.no

TØI Institute of Transport Economics, Norway

Follow us: